Friday, December 26, 2014

Thursday, December 25, 2014

Johnny Ace - Memorial Album (Early R&B Compilation 1961)

Bitrate: 256

mp3

Ripped by ChrisGoesRock

Artwork Included

Source: Japan 24-Bit Remaster

The senseless death of young pianist Johnny Ace while indulging in a round of Russian roulette backstage at Houston's City Auditorium on Christmas Day of 1954 tends to overshadow his relatively brief but illustrious recording career on Duke Records. That's a pity, for Ace's gentle, plaintive vocal balladry deserves reverence on its own merit, not because of the scandalous fallout resulting from his tragic demise.

John Marshall Alexander was a member in good standing of the Beale Streeters, a loosely knit crew of Memphis young bloods that variously included B.B. King, Bobby Bland, and Earl Forest. Signing with local DJ Mattis' fledgling Duke logo in 1952, the re-christened Ace hit the top of the R&B charts his very first time out with the mellow ballad "My Song." From then on, Ace could do no musical wrong, racking up hit after hit for Duke in the same smooth, urbane style. "Cross My Heart," "The Clock," "Saving My Love for You," "Please Forgive Me," and "Never Let Me Go" all dented the uppermost reaches of the charts. And then, with one fatal gunshot, all that talent was lost forever (weepy tribute records quickly emerged by Frankie Ervin, Johnny Fuller, Varetta Dillard, and the Five Wings).

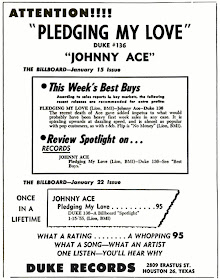

Ace scored his biggest hit of all posthumously. His haunting "Pledging My Love" (cut with Johnny Otis & His Orchestra in support) remained atop Billboard's R&B lists for ten weeks in early 1955. One further hit, "Anymore," exhausted Duke's stockpile of Ace masters, so they tried to clone the late pianist's success by recruiting Johnny's younger brother (St. Clair Alexander) to record as Buddy Ace. When that didn't work out, Duke boss Don Robey took singer Jimmy Lee Land, renamed him Buddy Ace, and recorded him all the way into the late '60s.

The senseless demise of Johnny Ace has historically overshadowed everything the young Memphis pianist accomplished while he was alive. That’s a tragedy unto itself.

Ace’s plaintive way of crooning an intimate blues ballad made him a fast-rising R&B star during the early 1950s. But his bright future evaporated with a single self-inflicted gunshot to the head backstage at Houston’s City Auditorium on Christmas night of 1954, an impromptu act that spawned an instant legend.

Born John Marshall Alexander Jr. on June 9, 1929 in Memphis, Johnny hailed from a large family headed by a Baptist preacher and a mother who never approved of her son’s blues exploits. According to James M. Salem’s book The Late Great Johnny Ace and the Transition From R&B to Rock ‘n’ Roll, the youth dropped out of eleventh grade to join the Navy (that tactic didn’t work out either). What Johnny enjoyed most was playing music. With wide-open Beale Street beckoning, he gravitated to its neon-lit nightspots during the late 1940s.

Johnny joined a loose-knit combo revolving around guitarist B.B. King; other key members were drummer Earl Forest and saxman Adolph “Billy” Duncan. “The group first was mine, and then it was called the Beale Streeters after that,” said B.B., then a local star thanks to his daily WDIA radio shift. “Johnny Ace was the piano player. His name was John Alexander, but he later started making records under his own name with the Beale Streeters. In fact, the whole group was the group that I put together when we made ‘Three O’Clock Blues.’”

The young pianist cut his first number as a leader in 1951 for Los Angeles-based Modern Records, the same label B.B. was on (co-owner Joe Bihari produced it at a session held at the Memphis YMCA), but “Midnight Hours Journey” wouldn’t see issue on their Flair subsidiary until after Ace began scoring hits for Duke. Since John waxed only one song for Modern, Forest’s “Trouble And Me” adorned the flip side.

King’s expanding popularity catapulted Johnny into a bandleading role. “When ‘Three O’ Clock Blues’ became a hit and I started to work out of a booking agency called Shaw Artists Corporation and Universal, they didn’t want me to have a band,” said King in 1979. “They wanted me alone. So I left the band, and when I did, I gave it to Johnny Ace. And that’s when he changed it. Instead of calling it the Blues Boys as it had been, he started calling it the Beale Streeters.”

Convinced that Memphis boasted a wealth of unrecorded black talent, WDIA program director David James Mattis inaugurated Duke Records in the spring of 1952. He selected Bland as one of his initial artists, but Bobby showed up at the ‘DIA studios unprepared to record. Mattis turned to Johnny, who was there to back Bland on the 88s. Johnny was fooling around with a blues ballad entitled “So Long” that had been a 1949 hit for Ruth Brown. Mattis and Alexander lyrically transformed it into “My Song.” Before issuing the 78 on his purple-and-yellow-hued Duke logo for local consumption, Mattis changed John’s stage handle to the sportier Johnny Ace.

Versions of Johnny’s first hit follow-up “Cross My Heart” were apparently cut in both Memphis and at Bill Holford’s Audio Company of America studios in Houston, but it appears that the Houston rendition was the one that climbed to #3 R&B on Duke in early ‘53. It was a mellow variation on “My Song” credited to Mattis and Robey, with Forest and bassist George Joyner accompanying Ace’s velvety vocal and flowery organ (he’d reportedly never played one prior to cutting “Cross My Heart” the first time at WDIA). Its B side “Angel” restored Ace to the piano bench but followed the same attractive late-night formula.

Johnny’s second R&B chart-topper “The Clock,” credited to Ace and Mattis, was waxed in January of ‘53 in Houston. The mournful ballad’s deliberate tick-tock percussion was courtesy of prolific bandleader Johnny Otis. Ace flexed his piano chops on the sax-led instrumental flip, “Aces Wild.” Otis’ octet backed Ace’s next chart entry, the intimate ballad “Saving My Love For You,” with Otis playing vibes at the August ‘53 Los Angeles date. Writer Sherman “Blues” Johnson was a Meridian, Mississippi product that had recently waxed two 78s for Lillian McMurry’s Trumpet Records with his Clouds of Joy. “Saving My Love For You” rose to #2 R&B in early 1954, coupled with “Yes Baby,” a rousing duet with labelmate Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton, who had paced the R&B hit parade in the spring of 1953 with her snarling “Hound Dog” (Pete Lewis contributed the stinging T-Bone Walker-style guitar solo to “Yes Baby”).

New Orleans blues shouter Joe “Mr. Google Eyes” August–one of Ace’s fellow Duke artists–came up with “Please Forgive Me,” a #6 R&B seller in the summer of ‘54 that deposited Ace behind the organ again as Otis’ L.A. outfit cruised behind him (Ace wrote the swinging B side “You’ve Been Gone So Long,” Lewis returning on slashing guitar). Duke/Peacock house trumpeter Joe Scott, soon to emerge as Bobby Bland’s musical mentor, composed the gentle pleader “Never Let Me Go,” Ace’s #9 R&B hit late that year. The swinging instrumental “Burley Cutie” was two years old by the time it was pressed into service as its flip.

Sadly, Johnny wouldn’t live long enough to bask in the monumental success of his next Duke platter. Credited to Ferdinand “Fats” Washington (he also co-penned the Flamingos’ “I’ll Be Home”) and Robey, “Pledging My Love” was a spine-chilling blues ballad that attained immortality in the shocking wake of Ace’s untimely death (an estimated 4500 mourners packed Clayborn Temple AME church in Memphis for his funeral services). Johnny’s tinkling piano introduction is answered note-for-note by Otis’ vibes before Ace’s warm baritone croon confidently enters to promise eternal devotion. Cut on January 27, 1954 in Houston with a smaller edition of Otis’ combo in support, “Pledging My Love” rocketed to the peak of the R&B hit parade in early 1955, managing a highly respectable #17 pop showing despite chirpy Teresa Brewer’s cover. A romping “No Money,” from Ace’s final Houston date in July of ‘54, supplied a mood-lightening contrast on the flip side.

A flood of maudlin tribute songs hit the market after Ace’s death, most notably Varetta Dillard’s “Johnny Has Gone” and Johnny Fuller’s “Johnny Ace’s Last Letter.” But the late Ace wasn’t done scoring hits of his own; “Anymore,” a Robey copyright waxed at the same January ‘54 session that generated “Pledging My Love,” rose to #7 R&B that summer (the torrid Ace original “How Can You Be So Mean” adorned the opposite side, its relentless horn section led by Johnny’s road band leader, saxist Johnny Board). Robey emptied his vaults to satisfy an ongoing clamor for more Ace product; “So Lonely”(an Ace composition that bore echoes of Charles Brown) and the classy “I’m Crazy Baby” were paired for one single (the latter was penned by C.C. Pinkston, who doubled on drums and vibes at Johnny’s final session), while a brokenhearted “Still Love You So” (another Washington/Robey collaboration) and the brassy Ace-penned strut “Don’t You Know” constituted Johnny’s last Duke outing. Robey wasn’t content to retire Ace’s franchise. He signed Texas singer Jimmy Lee Land and presented him as Johnny’s brother Buddy Ace (Buddy stayed on Duke for more than a decade and enjoyed a pair of mid-‘60s R&B hits).

In the end, Johnny Ace’s legacy shouldn’t be defined by a tragic game of Russian roulette. Remember him by these 20 splendid songs instead.

01. Pledging My Love 2:29 (1955)

02. Don't You Know 2:41 (1954)

03. Never Let Me Go 2:52 (1954)

04. So Lonely 2:33 (1956)

05. I'm Crazy Baby 2:16 (1956)

06. My Song 3:04 (1952)

07. Saving My Love For You 2:37 (1953)

08. The Clock 2:59 (1953)

09. How Can You Be So Mean 2:30 (1955)

10. Still Love You So 2:43 (1954)

11. Cross My Heart 2:46 (1953)

12. Anymore 2:58 (1955)

Bonus Tracks:

13. Yes Baby (With Big Mama Thornton) 2:46 (1953)

14. Please Forgive Me (1954)

15. No Money 2:45 (1955)

1. Johnny Ace

or

2. Johnny Ace

.

Tuesday, December 23, 2014

Sunday, December 21, 2014

Hour Glass - Power of Love (Great 2nd Album US 1968)

Bitrate: 256

mp3

Ripped by: ChrisGoesRock

Artwork Included

Source: Japan SHM-CD Remaster

Power of Love was the second studio album by Hour Glass, issued in March 1968 on Liberty Records, the final by the group with the namesakes of The Allman Brothers Band. After the failure of their first album, Liberty Records allowed a greater independence for the group, who had been virtually shut out of the decision making for their first album by the label and producer Dallas Smith. However, with the label's decision to retain Smith as producer, the group, especially Duane Allman, once again felt constricted by their label's expectations for the album.

With Smith behind the boards, Gregg Allman was still the focus. The younger Allman, who had seen only one of his compositions on the previous album, contributed seven of the twelve tracks. The remainder were two from Marlon Greene and Eddie Hinton and one each from the teams of Spooner Oldham and Dan Penn, John Berry and Don Covay, and John Lennon and Paul McCartney. The group performed all of the instrumentation, with Duane Allman adding electric sitar to their cover of The Beatles' "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)", a staple of their live act.

Neil Young of Buffalo Springfield wrote the liner notes, describing his experience sitting in on the session for the album track "To Things Before", watching Gregg Allman leading the group through the number.

After the failure of the album to enter the chart, the Hour Glass traveled to Fame Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, in an attempt to further refine their sound. However, Dallas Smith and Liberty Records were displeased with the group-produced blues-fueled rock tracks that the group returned to Los Angeles with, as they were light years away from the pop music Smith envisioned them performing. Additionally, seeing himself cut out of the group's picture was not ideal for Smith, even if his relations with the group had been strained.

Hour Glass disbanded shortly thereafter, with Gregg Allman returning to California to satisfy the terms of the group's contract with Liberty. Paired with a studio band, Allman recorded roughly an album's worth of material, though it took nearly a quarter of a century for it to surface. [Wikipedia]

Now this is a little more like it. The group really isn't sounding like they did at the Whiskey, but the playing by the band is pretty ballsy, and Duane's guitar is right up front and close, and he's showing some real invention within the restrictions of the pop sound that the producer was aiming for. He also plays an electric sitar on the strangest cut here, an instrumental cover of Beatles' "Norwegian Wood." From the opening bars of the title tune, one gets the message that this is a group with something to say musically, even if this particular message isn't it -- the guitar flourishes, the bold organ and piano by Paul Hornsby, and Gregg Allman's charismatic vocals all pull the listener better than 98% of the psychedelic pop and soul-pop of the period.

The outtakes that are included as bonus tracks are much more important, consisting of songs cut for a never-issued Gregg Allman solo album (intended to keep Liberty from suing over the group's breakup and departure), where he sounded a lot more like the lead singer of the Allman Brothers Band than he'd ever been given a chance to with the Hour Glass, on songs that included the future Allman Brothers classic "It's Not My Cross to Bear." [AMG]

Personnel:

♦ Gregg Allman – organ, piano, guitar, vocal (all tracks)

♦ Duane Allman – guitars, electric sitar (tracks 1-6, 8-12)

♦ Paul Hornsby – piano, organ, guitar, vocal (tracks 1-12)

♦ Johnny Sandlin – drums, guitar, gong (tracks 1-12)

♦ Pete Carr – bass guitar, guitar (track 7), vocal (tracks 1-12)

♦ Several unknown studio musicians on horns, guitars, backing vocals, drums, bass guitar, keyboards and percussion (tracks 13-18)

♦ Bruce Ellison - Engineer (all tracks)

01. "Power of Love" (Spooner Oldham, Dan Penn) - 2:50

02. "Changing of the Guard" - 2:33

03. "To Things Before" - 2:33

04. "I'm Not Afraid" - 2:41

05. "I Can Stand Alone" - 2:13

06. "Down in Texas" (Marlon Greene-Eddie Hinton) - 3:07

07. "I Still Want Your Love" - 2:20

08. "Home for the Summer" (Marlon Greene-Eddie Hinton) - 2:44

09. "I'm Hanging Up My Heart For You" (John Berry, Don Covay) - 3:09

10. "Going Nowhere" - 2:43

11. "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)" (John Lennon, Paul McCartney) - 2:59

12. "Now Is The Time" - 3:59

Bonus Tracks:

13. "Down in Texas" (alternate version) (Marlon Greene-Eddie Hinton) - 2:21

14. "It's Not My Cross to Bear" - 3:36

15. "Southbound" - 3:41

16. "God Rest His Soul" (Steve Alaimo) - 4:02

17. "February 3rd" (Composer Unknown) - 2:56

18. "Apollo 8" (Composer Unknown) - 2:37

All songs by Gregg Allman, unless noted.

Tracks 1-12 constitute the original album.

Tracks 13-18 from the 1969 sessions for Gregg Allman's unreleased first solo album for Liberty (present on 1992 re-release only).

1. Link

or

2. Link

.

.jpg)