Size: 117 MB

Bitrate: 320

mp3

Ripped by: ChrisGoesRock

Artwork Included

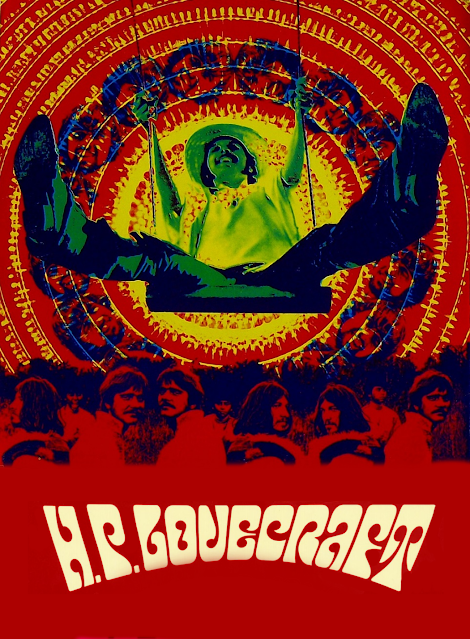

H. P. Lovecraft II is the second album by the American psychedelic rock band H. P. Lovecraft and was released in September 1968 on Philips Records. As with their debut LP, the album saw the band blending psychedelic and folk rock influences, albeit with a greater emphasis on psychedelia than on their first album. H. P. Lovecraft II failed to sell in sufficient quantities to reach the Billboard Top LPs chart or the UK Albums Chart, despite the band being a popular act on the U.S. psychedelic concert circuit. Legend has it that the album was the first major label release to have been recorded by musicians who were all under the influence of LSD.

Recording sessions for the album began in June 1968 at I.D. Sound Studios in Los Angeles, with the band's manager George Badonsky producing and British-born Chris Huston serving as audio engineer. H. P. Lovecraft had toured intensively during the first half of 1968 and consequently, there was a lack of properly arranged new material for the album. As a result, much of H. P. Lovecraft II was improvised in the studio, with Huston playing a pivotal role in enabling the underprepared band to complete the recording sessions.

Huston was also instrumental in creating the psychedelic sound effects that adorned much of the album's contents. The band's singer and guitarist, George Edwards, recalled the importance of Huston's contributions during an interview with journalist Nick Warburton: "Chris came up with a lot of very innovative techniques that prior to that record had not really been used. He was way ahead of his time. We had no material, the band was totally fried and Chris helped us make a record. That record would never have happened without Chris."

Among the tracks that were recorded for the album were the Edwards-penned compositions "Electrollentando" and "Mobius Trip", the latter of which featured lyrics that music historian Richie Unterberger has described as "disoriented hippie euphoria." In addition, the band elected to cover "Spin, Spin, Spin" and "It's About Time", which had both been performed by Terry Callier, an old friend of Edwards' from his days as a folk singer. Unterberger has remarked that both of these songs made effective use of the oddly striking vocal interplay and close harmony singing of Edwards and the band's keyboardist Dave Michaels.

The band's newest recruit, Jeff Boyan, who had only joined the group in early 1968 as a replacement for bassist Jerry McGeorge, was featured as lead vocalist on his own composition "Blue Jack of Diamonds" and on the band's cover of the folk standard "High Flying Bird". The track "Nothing's Boy" featured a contribution from voice artist Ken Nordine, and the cover version of Brewer & Shipley's "Keeper of the Keys" was issued as a single in late 1968, following its appearance on the album, but it failed to reach the charts.

The self-penned "At the Mountains of Madness" was based on the 1931 novella At the Mountains of Madness by horror writer H. P. Lovecraft, after whom the band had named themselves. Written by Edwards, Michaels and lead guitarist Tony Cavallari, the song featured some chaotically acrobatic vocal interplay and made ample use of swirling, echoed reverse tape effects, which served to highlight the song's sinister subject matter.

Release and legacy

H. P. Lovecraft II was released in September 1968. Critic Richie Unterberger has remarked that, despite being less focused than the band's first album, it nonetheless managed to successfully expand on the musical approach of its predecessor.[1] He also opined that it shared the haunting, eerie ambiance of the band's first album. Writing for the Allmusic website, Unterberger has described the album as, "much more progressive than their first effort", although he also noted that it "showed the band losing touch with some of their most obvious strengths, most notably their disciplined arrangements and incisive songwriting."

Although H. P. Lovecraft II failed to chart at the time of its release and had gone out of print by the early 1970s, a revival of interest in the band's music had begun by the late 1980s. This resulted in the album being reissued by Edsel Records, along with the band's debut album, on the At the Mountains of Madness compilation in 1988.

The album was again reissued in 2000, along with H. P. Lovecraft, on the Collectors' Choice Music CD, Two Classic Albums from H. P. Lovecraft: H. P. Lovecraft/H. P. Lovecraft II. In addition, the nine songs that make up H. P. Lovecraft II were included on the Rev-Ola Records compilation Dreams in the Witch House: The Complete Philips Recordings. (Wikipedia)

Like the stories of the author after whom they were named, H.P. Lovecraft’s music was spooky and mysterious, a vibe well-suited for the psychedelic times when their two albums were released in 1967 and 1968. Their remarkably eclectic balance of folk, jazz, orchestrated pop, and even bits of garage rock and classical music, was too fragile and ethereal to keep afloat for any longer than that, perhaps. It lasted long enough, however, for the group to gift us with two uneven, occasionally brilliant albums that are among the most intriguing obscure relics of the psychedelic age.

The band’s none-too-stable personnel were about as diverse as could be in the milieu of 1967 Chicago, not a city known for hatching top-flight psychedelic outfits. Guitarist George Edwards, the leader of H.P. Lovecraft if anyone was, had been a folkie in the early 1960s, entering the rock scene in the mid-1960s on the Windy City’s Dunwich label. He cut a single of the Beatles’ "Norwegian Wood," as well as a cover (not issued until the early 1970s) of Bob Dylan’s "Quit Your Low Down Ways" with Steve Miller on guitar. He also sang backing vocals on a couple of Shadows of Knight hits, yet by late 1966 was playing in a lounge jazz trio at a local Holiday Inn.

That experience did not go to waste, however, as another member of that trio was classically trained keyboardist and singer Dave Michaels. Michaels would sing backup vocals on the early 1967 single that served as H.P. Lovecraft’s debut release, "Anyway That You Want Me"/"It’s All Over for You" (added to this CD as bonus tracks). Essentially a vehicle for Edwards, the A-side was a fair pop-rock tune by Chip "Wild Thing" Taylor (which was a hit in the UK for the Troggs). The Edwards original on the flip was actually a solo outtake from 1966, sounding like a raw folk-rock derivation of Dylan’s "It’s All Over Now Baby Blue." Edwards and Michaels, however, determined to form a more permanent and ambitious H.P. Lovecraft lineup over the next few months. This eventually settled into the quintet of Edwards, Michaels, guitarist Tony Cavallari, drummer Michael Tegza, and bassist Jerry McGeorge (who had been rhythm guitarist in the Shadows of Knight). In late 1967, this lineup recorded and released their self-titled album, a wide-ranging mixture of covers and originals that unveiled a far more striking vision than had been apparent on the single.

The group’s strongest asset was the superb dual harmony lead vocals of Edwards and Michaels, showcasing Michaels’ operatic four-octave span with a blend reminiscent of the Jefferson Airplane. Michaels’ multi-instrumental virtuosity on organ, harpsichord, piano, clarinet, and recorder-often bolstered by session players on horns, clarinet, piccolo, and vibes-gave the band a much wider range of timbres than much of their competition. Their seeming determination to plough different ground with every cut sometimes misfired, as with the too-cheerful version of Dino Valenti’s "Let’s Get Together" and the hokey old-time music of "The Time Machine." More often, though, H.P. Lovecraft devised a haunting ambience that lived up to their pledge on the back sleeve to make songs inspired by (author) H.P. Lovecraft’s "macabre tales and poems of Earth populated by another race."

Most of the songs on H.P. Lovecraft, however, were not originals, but folk-rock covers. The Edwards-Michaels vocal blend was particularly stirring on their covers of "The Drifter" (penned by folkie Travis Edmonson, half of the duo Bud & Travis) and the folk standard "Wayfaring Stranger." Their debt to cult folk-rocker Fred Neil was expressed in a gutsy, hard-rocking version of that singer-songwriter’s "The Bag I’m In," as well as "Country Boy & Bleeker Street," which combined two songs from Neil’s mid-1960s solo debut album. "I’ve Been Wrong Before," by a then-little-known Randy Newman, had already been done by Cilla Black (who had a British hit with the tune), Dusty Springfield, and California garage band the New Breed; H.P. Lovecraft gave it a particularly mystical, enchanting reading.

Yet the finest song H.P. Lovecraft ever did was the group composition "The White Ship." The six-and-a-half-minute opus had a wavering, foggy beauty, with some of Michaels’ eeriest keyboards, sad dignified horns, lyrics that fit in well with the album’s constant references to drifting and wandering, and even the ringing of an "1811 Ship’s Bell" (by Bill Traut). In yet another stylistic twist, Edwards and Michaels put their lounge jazz chops to good use on the suave but moody "That’s How Much I Love You, Baby (More or Less)."

By the time H.P.Lovecraft II came out in September 1968, the group had replaced McGeorge with bassist singer Jeff Boyan; moved from Chicago to Marin County; and shared bills with Donovan, the Pink Floyd, Procol Harum, the Jefferson Airplane, the Buffalo Springfield, Big Brother & the Holding Company, and other top psychedelic acts. Their music had become more psychedelic, but also less focused and more self-indulgent, sounding at times like an acid trip starting to go awry. This prevented the album from being the equal of its predecessor, though at its best it still packed quite a punch.

Michaels’ keyboards in particular were moving into gossamer spaciness that undoubtedly made H.P. Lovecraft a good match for sharing the bill with Pink Floyd. (Not released until the 1990s, the Live May 11 1968 album proved that H.P. Lovecraft, unlike many psychedelic bands with mighty ambitions, could execute their complex arrangements well in concert.) "At the Mountains of Madness" was certainly a highlight of the group’s psychedelic free flights, skittering close to, but never falling into, an abyss of menacing distortion-ridden chaos, with especially acrobatic vocal tradeoffs. "Mobius Trip" gave the lounge jazziness of "That’s How Much I Love You, Baby (More or Less)" a far, well, trippier gloss, its vocals evaporating into the mist at the end of the verses, its lyrics soaked in disoriented hippie euphoria.

More disorganized outings like "Electrallentando," however, indicated that the drug experience might be getting the better of them. "Keeper of the Keys" had a pseudo-operatic vocal so stentorian that it was difficult to tell if it was over-reaching earnestness or parody. (The forty-second Zappaesque link "Nothing’s Boy," by the way, was written by radio wordjazzmeister Ken Nordine, who also provided the spoken narration.)

For all its ephemeral weirdness, H.P. Lovecraft II looked back to folk music with its radical psychedelic reinterpretation of Billy Wheeler’s "High Flying Bird," the early folk-rock classic that had been recorded by Judy Henske and the Jefferson Airplane. There were also adept close-harmony covers of "Spin, Spin, Spin" and "It’s About Time," both of which utilized Michaels’ flair for classical-flavored keyboard lines. The latter of these had especially Airplane-ish vocalizations and almost tortuous shifts of musical settings, veering between dissonant psychedelia and strident strings. Both songs were written by Edwards’ friend Terry Callier, the folk-jazz singer whose cult was small enough to make Fred Neil’s following seem huge. (Callier, incidentally, had recorded "The Drifter," as "I’m a Drifter," in the mid-1960s, prior to H.P. Lovecraft; Edwards would co-produce a half-dozen of Callier’s tracks in late 1969.)

Although H.P. Lovecraft were well-received on the psychedelic concert circuit, neither of their two albums sold well enough to make the charts. Edwards has recalled (in Ptolemaic Terrascope magazine) that the second LP was something of a rush job, without as much time for writing or recording as they would have liked. Dissension and the pressures of touring caused the band to split in 1969. Although Edwards and Tegza did re-form the group in 1970, Edwards left before their album came out, by which time the band were simply called Lovecraft, and bore little musical resemblance to the H.P. Lovecraft of the 1960s. A final Lovecraft album came out in 1975. But the true H.P. Lovecraft, of psychedelic sailors on white ships drifting on who knows what uncharted waters, is contained on this CD, which includes all of their 1960s studio recordings. (Richie Unterberger)

Musicians:

♦ George Edwards – vocals, acoustic guitar, electric guitar, bass

♦ Dave Michaels – vocals, keyboards

♦ Tony Cavallari – lead guitar, vocals

♦ Jeff Boyan – bass, vocals

♦ Michael Tegza – drums, percussion, vocals

01. "Spin, Spin, Spin" (Terry Callier) – 03:21

02. "It's About Time" (Terry Callier) – 05:17

03. "Blue Jack of Diamonds" (Jeff Boyan) – 03:08

04."Electrallentando" (George Edwards) – 06:34

05. "At the Mountains of Madness" (George Edwards, Dave Michaels, Tony Cavallari) – 04:57

06. "Mobius Trip" (George Edwards) – 02:44

07. "High Flying Bird" (Billy Ed Wheeler) – 03:21

08. "Nothing's Boy" (Ken Nordine) – 00:39

09. "Keeper of the Keys" (Mike Brewer, Tom Shipley) – 03:05

1. H.P.

or

2. H.P.

or

3. H.P.

I was lucky enough to actually see them live. Great show opening for Spirit at the Fillmore East. Both bands were shockingly great.

ReplyDeleteThanks Chris. Much appreciated.

ReplyDeleteWow! This is impressively good! Thank you, Chris!

ReplyDelete